Sigma Pi Sigma — A Departmental Legacy of Fellowship

Spring

2022

Unifying Fields

Sigma Pi Sigma — A Departmental Legacy of Fellowship

Part 5: The Contribution of Federal Science Policy to SPS and Sigma Pi Sigma

By:Jack Hehn, Senior Fellow, American Association of Physics Teachers and Director of Education (Retired), American Institute of Physics, and Brad R. Conrad, Director of SPS and Sigma Pi Sigma

The development of federal science policy in the United States after World War II spurred not only the physics and astronomy curriculum as we know it today, but also the decades-long growth of both university research and the undergraduate ecosystem of SPS and Sigma Pi Sigma chapters. From 1945 to 1965 there was significant interest in and support for science in the United States, particularly for academic science. At the same time, the United States undertook a great deal of infrastructure improvement projects and supported more and broader education.

Part of the reason was that, coming out of World War II, the United States had the resources and pent-up demand to release a consumer economy that had been destroyed in so much of Europe. The United States was suddenly recognized as a “great world power.” These factors influenced government support for science and technology and their wide recognition in national media, which led to the popularization of science and technology in general.

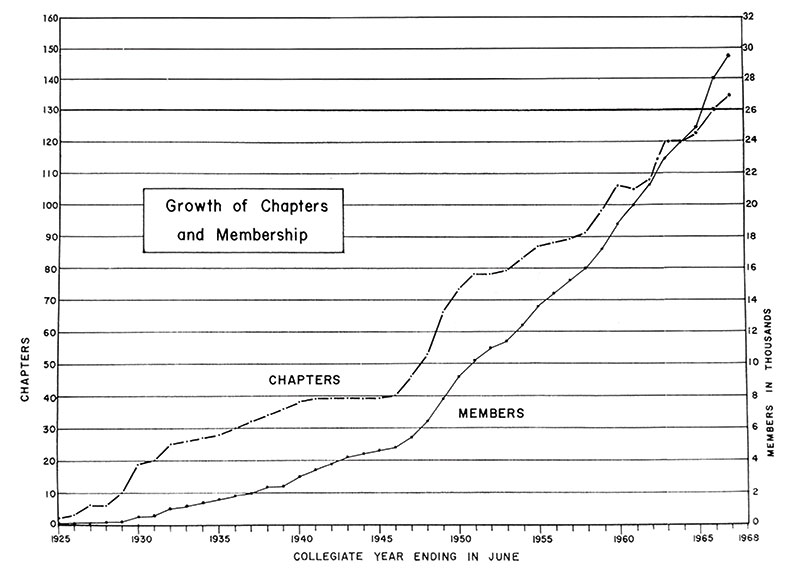

America started to become a world resource in scientific fields, creating the necessity of a much larger scientific workforce. This prompted a significant increase in federal investment in science and engineering education. And, in turn, to a rapid rise in Sigma Pi Sigma membership.

Much of this systematic and consistent government support was influenced by the Vannevar Bush report, “Science, the Endless Frontier.” Bush was director of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development. In November of 1944, President Roosevelt sent a letter to Bush requesting recommendations on how to proceed with the nation’s science efforts now that the war was over. In closing he wrote, “New frontiers of the mind are before us, and if they are pioneered with the same vision, boldness, and drive with which we have waged this war we can create a fuller and more fruitful employment and a fuller and more fruitful life.”1

Bush responded in July of 1945 to Truman, who became president when Roosevelt died in April. Bush’s document became the guiding narrative for the US scientific enterprise for decades to come. The report included appendices from distinguished committees: the Medical Advisory Committee, the Committee on Science and the Public Welfare, and the Committee on Discovery and Development of Scientific Talent.2

The mobilization of American industry in response to the war and the resulting new development of scientific knowledge and processes led to new advances against disease, in strategic defense, and in recognition of the public welfare and an improving quality of life for every citizen. The Bush report opines that these advances could only have been built on the knowledge provided by basic scientific research.

Most of the physics done during the war was applied science, largely carried out by academic faculty and students working as industrial or military personnel under federal contracts. Before the 1940s, most academic work in science, engineering, and medicine had been supported by endowments, foundation support, and private donations. The Bush report recognized a fundamental change in perception—the quality of life of the average citizen could and should be enhanced by government support of basic research. In short, basic science ought to be financially supported for long-term gains.

The federal government was ready to accept the responsibility for developing scientific knowledge and a scientifically talented labor pool among young Americans. One of the first policy recognitions was a dramatic need for all people to be educated in science, including physics and “space-oriented” subfields. A second policy recognition was the need to support basic research principally conducted on university and college campuses as an integral part of undergraduate and graduate programs. The Bush report advocated for the formation of a new federal agency, which became the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1950. An important factor in these policies was that the decisions about federal support of basic science must be based on the advice of academic scientists more than that of federal bureaucrats.2

In the years following World War II, there was both a baby boom and a large number of men in uniform that were mustered out into the transitional economy. For many years the government had wisely supported academic institutions through the Morrill Act (1862) and the development of the Land Grant Colleges system. Building on this premise of federal support to universities, a federal program called the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill, was created for World War II veterans. This bill funded the construction of additional VA hospitals, made mortgages more accessible, and established funds to cover tuition for veterans attending college. There developed in many universities larger and broader colleges of science and engineering to meet this student and labor demand. Physics departments were an important part of this growth. As far back as at least 1966, statistics on physics and astronomy departments were sent to chapters within Sigma Pi Sigma.

There followed a recognition at the NSF in 1956 that science education should be dramatically increased in the public schools so that an interest in science could be developed within families and the science talent pool could be developed at an earlier age. To review and implement improvements to introductory physics education, the Physical Science Study Committee (PSSC) was created at a 1956 conference at MIT. This led to the production of an entire series of instructional movies, textbooks, and laboratory materials widely used in high school classrooms around the world for the following decades.

NSF continued supporting a number of science curriculum development programs (abbreviated as BSSC, Chem Studies, ECCP, ISIS) that emphasized summer institutes on college campuses, providing more in-depth science education for teachers. The teachers took information from these summer institutes directly back into their classes. The NSF also supported summer activities on college campuses for high school students to develop their interests and career aspirations in science and technology.

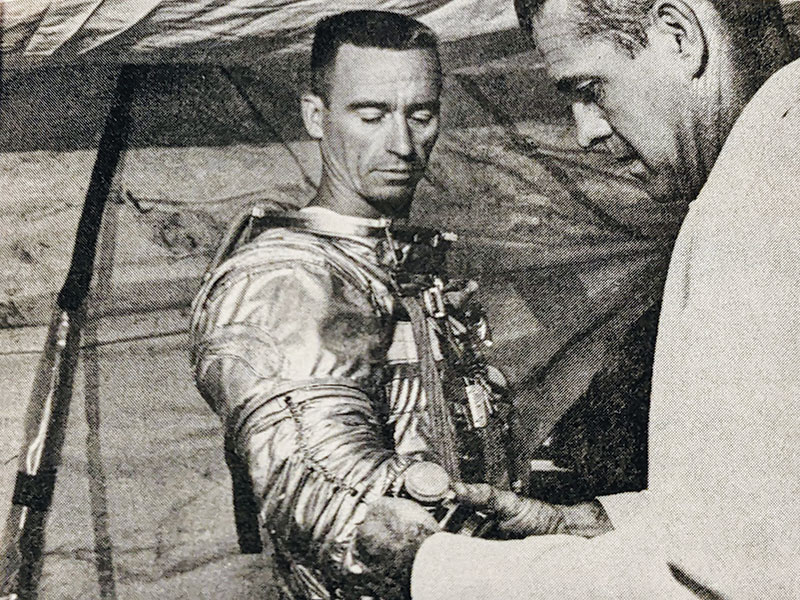

In 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established when President Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act. This new civilian agency was tasked with institutionalizing America’s efforts in space exploration.

NASA was created to respond to the launch of the Soviet Union’s Sputnik I on October 4, 1957, the first artificial satellite successfully placed into orbit. This launch caught everyday Americans by surprise and signaled the beginning of the US–Soviet “Space Race,” as the White House saw a clear need to demonstrate technological superiority. While embarrassing for officials, this also began an era of rapid technological development and continued investment in science and engineering.

Public information and public understanding have been a fundamental undertaking for NASA, particularly through the Apollo project in the 1960s. NASA estimates that a total of 400,000 people across the United States were involved in the Apollo program. These developments and an influx of both funding and interest in physics can be seen in publications at the time. The November 1963 issue of Radiations states, “The National Aeronautics and Space Agency plans to increase sixfold the number of graduate students subsidized to study ‘space-oriented’ subjects. The goal is to double the number of PhD graduates by 1970, as compared with present productions. These expanded enrollments will materially increase the number of potential members for the chapters of the Society.”3

Sigma Pi Sigma started in 1921 and grew steadily before WWII. It would be remiss to not mention that well before World War II, historians and sociologists documented Americans as a “nation of joiners,” particularly before 1940.4 After WWII (1946–1967) there was huge growth in the number of Sigma Pi Sigma chapters, so much so that the number of zones the chapters are divided into jumped from 10 to 19.3 Some of this growth may have been driven by federal science policy and national support for science. After the glow of the space race faded, NASA continued to make a significant impact on many college campuses, primarily through the National Space Grant College and Fellowship Project, also known as the Space Grant, created in 1989. Space Grant is a national network of colleges and universities. In addition to doing research, many Space Grant colleges administer pre-college and public service education projects in their states.

Many of us who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s remember an era and an environment when science offered many exciting new and rapidly expanding opportunities. We saw science nightly in the national TV news, in popular magazines and newspaper headlines, and even newspaper sections, heard our teachers’ excitement about new opportunities to teach science, and experienced summer opportunities to attend NSF workshops for students and teachers. It is no surprise that so many people in that cohort have lived careers in science and education. It has been a great adventure for us, and federal support has been essential.

The authors wish to thank Rachel Ivie, AIP Senior research Fellow, for valuable contributions and discussions.

References

1. “President Roosevelt’s Letter,” in Science, the Endless Frontier: A Report to the President (July 1945), www.nsf.gov/od/lpa/nsf50/vbush1945.htm#letter.

2. Vannevar Bush, Science, The Endless Frontier (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021).

3. Radiations of Sigma Pi Sigma, XXV, no.1, November 1963.

4. Gerald Gamm and Robert Putnam, “The Growth of Voluntary Associations in America 1840-1940,” J. Interdiscip. History, XXIX, no. 4 (Spring 1999): 511–577.

Read More

This article is Part 5 in “Sigma Pi Sigma – A Departmental Legacy of Fellowship,” a series highlighting the history of Sigma Pi Sigma and SPS in celebration of our centennial. The rest of the series is available online.

Part I: Formation and the Early Years

www.sigmapisigma.org/sigmapisigma/radiations/issues/fall-2019

Part 2: A Phase Change in the Late 1920s

www.sigmapisigma.org/sigmapisigma/radiations/issues/spring-2020

Part 3: Developing Community (1930s & ’40s)

www.sigmapisigma.org/sigmapisigma/radiations/issues/fall-2020

Part 4: SPS — A Society for All

www.sigmapisigma.org/sigmapisigma/radiations/spring/2021