Art Captures How Rockets Feel Forces

Fall

2016

Connecting Worlds

Art Captures How Rockets Feel Forces

Andrew Silver

About 350 years ago, as the story goes, an apple fell near British physicist Isaac Newton and planted the seeds of the laws of motion. Now, in celebration of that anniversary, retired math teacher Stan Spencer has borrowed what Newton learned to create art from simulated rocket motion and get others interested in understanding science.

“I tend to have a sort of crazy idea like that and then go for it,” said Spencer, who lives in Nottinghamshire, England.

After the apple incident, Newton started thinking about how objects in the universe move. He came up with laws for motion and gravitation still taught in high school physics classrooms today. They help explain how Earth’s gravity pulls apples to the ground or GPS satellites into orbit.

In particular, Newton found that bodies with mass appear to tug at one another. The force of those tugs grows stronger as masses increase or as distances get shorter. Ever curious, he formulated equations that describe the strength of this invisible force.

Newton’s laws start breaking down when explaining motion near the speed of light and the behavior of very large or very small, atom-sized objects.

“But he’s good enough to get you to the Moon and back,” Spencer said.

In his work, Spencer visualized the motion of a rocket, which can use the gravitational pull of nearby planets to save expensive fuel. Each planet’s gravitational force can guide a spacecraft so that it arrives at its destination more quickly and efficiently than it would if traveling only by its own power.

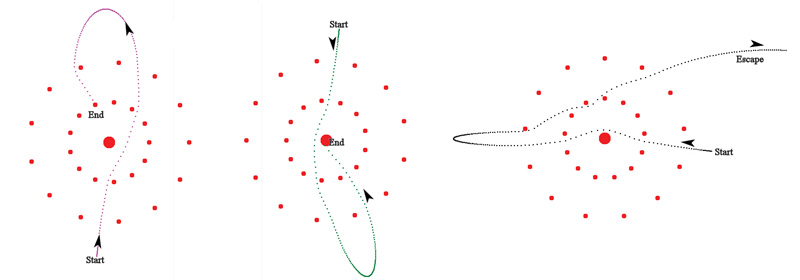

The images are created from a series of equations that simulate virtual rocket trips around a series of masses. For a given image, Spencer sets up digital circles in patterns representing rings of planets around a star or stars in constellations. Then, the computer program checks what happens when a rocket is launched from each spot on the digital canvas, one by one, factoring in the pull of the objects in the circles on each launch.

Each “rocket” eventually hits a mass or flies off the screen. Its starting position is assigned a color based on the mass it hit, and the intensity of the color changes depending on how long the trip took.

The setups aren’t a particularly practical application of Newton’s laws for a spaceship, explained Spencer. “But, you know, you might get some interesting pictures out of it.”

Spencer tested different mass arrangements and color choices, producing various symmetric, swirling patterns around the circles.

“The pictures—they were a surprise, really,” he said. “I didn’t know what was coming until it came.”

He presented the research at the annual Bridges Conference on mathematics and art in Jyväskylä, Finland, on August 10, 2016.

“I see that very much as something that could be used on a high school level as an exercise and as a motivational, inspirational example,” said Andres Wanner, a physicist and digital artist at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Switzerland. He was not involved in Spencer’s work.

“It shows the symmetry of physics laws, which is something that nonscientists often miss because it’s buried in the math,” said Elizabeth Freeland, a physicist at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, who was also not involved in the work.

She said she would share the work with her art students, who might get inspired to explore similar projects with some help.

“Seeing somebody land on the Moon isn’t going to turn you into an astronaut,” Freeland said. “But it might make you say, hey, I want to learn more about that.”

Spencer said the next step of the project is to experiment with randomly placed, not symmetrically arranged, circles. He’s also continuing to explore other art visualizations from math and physics.

“If it encourages people to ask the questions,” he said, “then to some extent you’ve created interest.”