I Traded Grad School for Life Without WiFi

Fall

2023

Feature

I Traded Grad School for Life Without WiFi

Victoria Catlett, Software Engineer, Green Bank Observatory

I had planned to be in graduate school right now. Instead, I’m in a place where WiFi is illegal and the nearest Walmart is an hour away. My phone stays in airplane mode—there’s no cell service. I wouldn't want to be anywhere else.

I graduated last year from the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD), where I earned bachelor’s degrees in physics and mathematics. While there I spent a lot of energy making sure that I was doing the exact right things to get into a good graduate school. I planned to get a PhD and then… well, I’d have at least five or six more years to figure that out. But when I stared at the blank graduate school application forms, I couldn’t bring myself to commit to more schooling.

I liked the coding I’d done in classes and research, so I started looking for software jobs. I doubted I’d get a job in a field I didn’t have a degree in, but I tried anyway.

Then, in January of my senior year, I got the offer that brought me here: a software engineering position at the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia, home of the world’s largest fully-steerable radio telescope.

The observatory, and the surrounding area, has strict rules prohibiting radio-emitting devices because they interfere with the telescope’s sensitive observing work (and that of the nearby National Security Agency site)—hence the lack of WiFi and cell service.

Green Bank seemed like a strange place to live, and the job didn’t match my major, but I accepted because it sounded like a fun challenge. It ended up being the perfect move for me! I help with all sorts of groundbreaking science while learning new skills and drawing from my existing skill set.

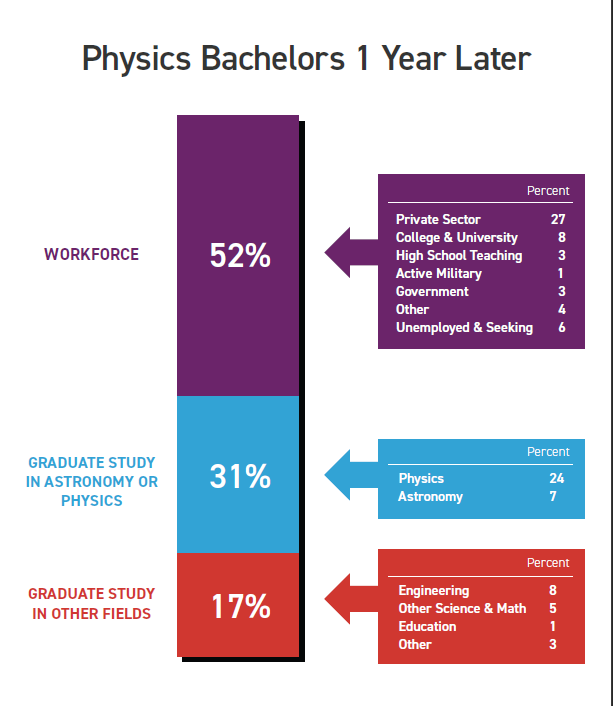

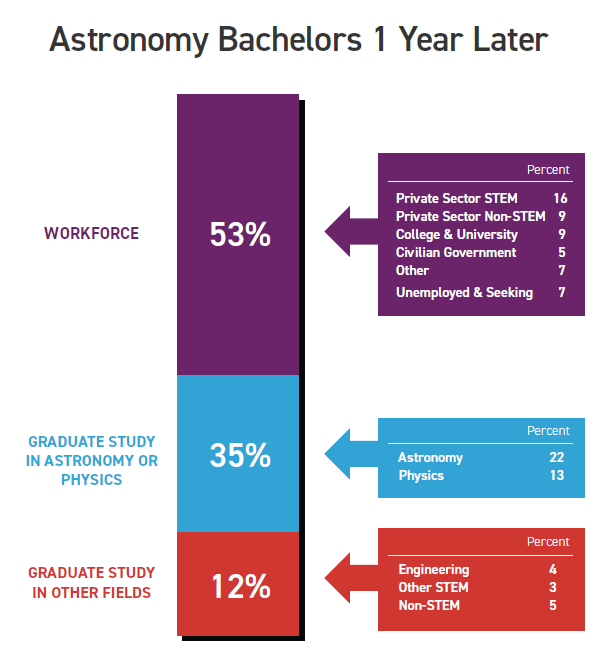

My experience is actually quite common. According to the American Institute of Physics (AIP), about half of the physics and astronomy majors in the United States go directly into the workforce after earning their bachelor’s degrees. And most of their jobs don’t have “physics” or “astronomy” in the title!

The problem-solving skills physics and astronomy students learn are transferable to a wide variety of fields. That’s one of the great things about the degree. Most jobs rely heavily on on-the-job learning, and many employers want to hire people who know how to break down problems into their constituent components.

I’m sharing my story with the hope that I can help others find the right path, like I did. The last year of college can be incredibly stressful, with advanced classes, deciding what to do next, applying for programs or jobs, and awaiting your fate. In physics and astronomy, many majors don’t know a lot about options beyond graduate school.

Here are some resources that can help you figure out what’s next:

- SPS Careers ToolBox: The Careers Toolbox contains helpful information and practical tools for undergrads who are considering going right into the workforce after college. Check it out at spsnational.org/sites/all/careerstoolbox.

- Common Job Titles for Physics Bachelors: The AIP Statistical Research Center compiles a list of common job titles held by physics bachelor’s degree recipients. Browse the list at aip.org/statistics/common-job-titles-physics-bachelors.

- Job listings from professional organizations: Most large professional societies maintain lists of active job openings relevant to people in their fields, including SPS (jobs.spsnational.org), AIP (through Physics Today, jobs.physicstoday.org), and the American Astronomical Society (AAS, jobregister.aas.org). They’re helpful for exploring the possibilities and job hunting.

- Who’s Hiring Physics Bachelors? If you know where you’d like to live, check out this state-by-state listing of employers who recently hired new physics bachelor’s degree recipients, aip.org/statistics/whos-hiring-physics-bachelors.

Once you have an idea of what you want to do, this is what I suggest:

- Write (and maintain) a CV: A curriculum vitae (CV) is essentially a long version of a résumé detailing your academic and professional experiences. When you have everything in one place, you can easily send prospective employers the entire CV (if they ask for it) or create a custom, single-page résumé by plucking out the most relevant information.

- Tailor your online presence: Your online presence isn’t just about your public social media accounts, although you should make sure they are professional. The internet gives you options to cultivate your image in ways that are more flexible than a résumé. For example, if you’ve done programming, make a few clean, well-documented GitHub repositories of your work.

- Learn from real people: The day-to-day work of a job is almost certainly not what you envision. Talk to people who took various paths—those you’re interested in and those you’re not! You might be surprised about the realities of certain paths.

Figuring out the next step in your life can be scary, but armed with the right information, you’ll do just fine. Be open to possibilities outside of your plan, and you may find exactly where you’re supposed to be.